How to Reply to Reviewers

May 2025

Assume reviewers and editors have good intentions.

There is a tendency to assume reviewers (and sometimes editors) are “out to get you” and make your life difficult. In fact, most people have good intentions.

Reviewers take a lot of unpaid and underappreciated time to critically evaluate your work. Good reviewers and editors aim to maintain high standards for the field, to ensure the claims of a manuscript don’t go beyond the data, and to help the authors make the paper better and clearer than it would otherwise be. Even reviewers who are hostile or clueless or unclear can lead you to improve the manuscript.

Grant reviews that seem “nit picky” may be an artifact of the system. For highly competitive grants (e.g., 10-15% success rate, like CIHR or NIH), there will be many more grants that deserve funding than funds available. Reviewers may in fact not have found any major flaws in your proposal and may need to focus on minor flaws that may or may not have really made a difference. But at least they are trying to give you some feedback in a noisy system.

Read the editor’s letter carefully

Editors who do the minimum will “count the votes” from reviewers as to the outcome, make a decision and send out a boilerplate letter with the reviews appended. Even here, the choice of the decision tells you a lot about your options:

1. Accept with minor revisions (or rarely no revisions)

The best possible outcome, albeit rare for a first submission.

2. Major revisions required

This is the most common outcome for standard journals.

3. Reject with possibility of submission as a new manuscript

When “major revisions are required”, the expectation may be that if the revisions are made, the manuscript will be publishable.

Alternatively, there can be cases where it may not be clear whether the revisions would be sufficient for the manuscript to be considered acceptable. As one example, reviewers could request an additional control analysis and only consider the manuscript publishable if a confound is ruled out. In these cases, the editor may explicitly tell you that publication after revision is not guaranteed or may even reject and ask you to resubmit as a new manuscript.

4. Reject without opportunity to resubmit

This may seem like the worst outcome, but it can be better than endless revisions.

Editors who go beyond the minimum duties will read or at least skim your paper and read the reviews carefully in order to give you clear guidance as to what steps are essential in a major revision. They may for example tell you that one recommendation from a reviewer is essential while another is optional

Read the editor’s letter very carefully.

Take some time to think and blow off steam before replying.

Your gut reaction to receiving reviews will be to get annoyed and go on a tirade against the reviewers, editor, and journal about how stupid they are for not immediately recognizing your brilliance. This is natural and you should allow some time for this. However, never respond when you’re in this state. After you’ve ranted to your co-authors, waited at least a day and cooled down, and reread the reviews, you will be more open to the constructive criticism they can provide.

Take the reviewers’ concerns seriously and respectfully.

Don’t be hostile to the reviewers, even if their tone strikes you as hostile. Also don’t be unnecessarily subservient and sycophantic.

One trend I’ve noticed over many years of reviewing and editing is that some labs do the bare minimum possible, “phone it in”, on reviews, while the best labs are diligent about seriously addressing reviewers’ comments, sometimes going above and beyond expectations. Even though you might squeak through with a minimal response, consider which kind of reputation you want to acquire among your colleagues.

Wherever appropriate, change the manuscript to accommodate a reviewer’s point

If your reviewer made a good point that other readers might also raise, address the point in the manuscript itself. Do not just address concerns with a long-winded answer in the reply to reviewers.

If you think that the point was idiosyncratic to the reviewer, you may choose to address it only in the reply to reviewers.

Unless the whole manuscript was completely revamped, paste the changed manuscript text in the reply.

As a time-pressed reviewer who receives a revision, I would much prefer to see the text that has been changed in the reply than to have to read the reply and reread the paper. This way, I can see quickly whether my points have been addressed satisfactorily.

This strategy is also beneficial to the authors. If you force the reviewer to reread your manuscript, that increases the probability that they will think of new critiques and prolong the review cycle.

Use different font styles to distinguish the reviewers’ comments, your response, and text extracts.

Most journals will ask you to submit a version of a Word document with “track changes” as well as a “clean” version (with tracked changes accepted).

Less is more

Edit your reply to be concise. Don’t paste changed text and give a redundant explanation of the changes.

If your reply is long and rambling, the reviewer may conclude it’s not worth the time to unpack and just reject the paper.

As with any writing, take the time to edit your responses carefully multiple times with breaks in between.

When reviewers are confused, make your manuscript clearer

Reviewers may raise points because they didn’t understand something. Rather than belittling them for failing to understand, revisit your manuscript and see what you could make clearer so that other readers don’t fall prey to the same misunderstanding.

Often, you may have implicit logical arguments that you need to make explicit.

If you don’t understand a reviewer’s comment, admit it

Reviewers may be in a rush and not always clear. You can admit when you don’t get it. You can also say things like, “We assume the reviewer meant X, in which case…”

You can choose whether to cite all the recommended papers

Sometimes you will get reviewers who ask you to cite everything they’ve ever written since their 7th grade report on otters. You can choose to include only the citations that are relevant and justify your decision to the editor.

Appeal only in extreme cases.

Like appeals from whinging undergrads about their grades, appeals from authors can be very time consuming and annoying. Don’t be “that person” who makes the editor hate their job and declare you a whiner.

Though it is possible to appeal to the editor, do so only when you have very strong arguments that a misjustice occurred or that a reviewer was unfairly biased on completely misunderstood the crux of the research.

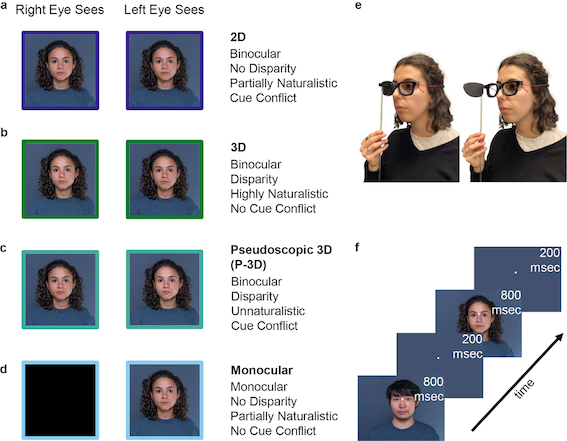

Former honours student and current research assistant Sofia Varon got her first publication: Target interception in virtual reality is better for natural than for unnatural trajectories